When a male Carolina Mantis showed up on my balcony a few days ago, perched upon a an old raggedy towel covering the back of a metal folding chair I use as a makeshift tricep dip bar, I knew the poor fellow was living out his final few days before succumbing to the inevitability of his rapid lifespan. Stepping outside and seeing the predatory invertebrate was a bit jarring at first; I remember seeing mantises in my childhood suburban backyard roaming around the grassy expanse or perched atop a bird feeder patiently waiting to snarl its dinner. But no one can expect to see the species in an urban environment. Like a hooker soliciting outside of a nunnery, he didn’t belong here, and I wondered why he found shelter in my humble abode. Perhaps he was seeking refuge from the brewing wind and rain that was soon to engulf the stormy September sky (animals notoriously have a keen sense of bad weather after all). I first attempted to shoo him away - surely he wanted to be somewhere greener and more plentiful than the concrete slab attached to my unit that was primarily used as a locale for an occasional drunken cigarette. Somewhere where he could frolic and hunt and ambush and terrorize local bee populations. This was to no avail, as unfortunately he had the typical insectile gait you see when a specimen is about to die - decrepit movements, non-existent reaction times to a waving human hand that would normally send it into a fight or flight frenzy, and an overall lethargy and discontent toward the surrounding environment. So realizing he was there to dig his own grave, I moved him from the chair to a cozier location inside a metal bucket in the corner of my balcony. I attempted to feed him a dead fruit fly, but he took no interest in my supper offerings.1 And as I observed and interacted with my new friend, I had a stark realization about something morbid - it was mating season.

If you don’t know what mating season means as it pertains to the order Mantodea, I encourage you to do a quick Google search. But if you do not wish to indulge yourself, I will do so for you: mating season in the microscopic world of the mantis often means death, destruction, and even cannibalism, all necessary for the survival of the species. Around this time of the year, September and October, males and females will seek each other out, often the former searching for the latter, hoping to find a suitable partner that will guarantee the continuation of favorable genetics so that praying mantises can continue to exist in this ever-dynamic and increasingly competitive and ecologically complex world. Those poor males have no idea what fate they might face. After a coital period that can last up to 18 hours (not even a gas station dick pill or Viagra prescription could keep your member stiff enough for this), female mantises may decide that the impregnation made them hungry, and will proceed to devour their mate as some sort of diabolically twisted pregnancy snack.2 So much for ice cream and pickles.

Although my mantis friend was dying, he was a survivor. Maybe he got lucky. Or maybe he hadn’t been so lucky but managed to escape his female surrogate nonetheless. Regardless, in a few days he would be dead. His biological clock was set to expire. Mantises can live up to 3 years in captivity, with proper nutrition and habitation, but in the wild they will be lucky to last a year. My friend’s hatchlings will spawn next spring, emerging from an egg sac known as an ootheca, and quickly evolve from nymph to adult in just a few months. The warming temperatures and blossoming flowers will bring out the mantis’s favorite foods, and for a few months, they will thrive in a utopia of abundance. By the time the mantises are half a year young, the weather will once again turn, and instincts will lead them towards finding a suitable mate, where they will risk succumbing victim to cannibalism. If they are lucky, they will escape to a random balcony in the city and live out their final days in the comfort of a shielded palliative care center. How the circle of life is so beautiful and brutal.

A few days later, I found my mantis friend dead, and in reflection on his untimely demise, I found myself thinking: wouldn’t life as a human being be so much simpler if we expired a few weeks after fornicating? Although in a way I suppose that already occurs, at least spiritually. Here’s to the praying mantis. May one day, after the world is turned to ash, you patrol the ruins as guardians of what remains.

Onwards,

Tony

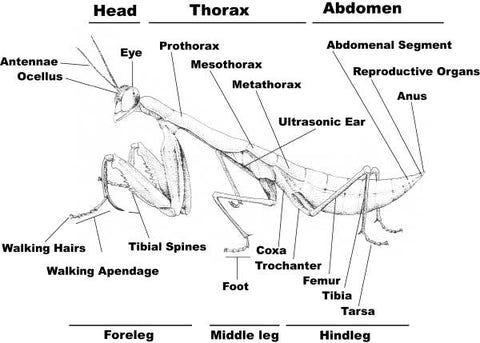

Which was stupid to even offer him in the first place, as praying mantises are tried and true ambush predators, and will not touch prey that they did not hunt and catch themselves. In fact, mantises have a fairly sophisticated sense of vision and overall spacial awareness that allows them to both capture flying objects at relatively high speeds, as well as elude incoming predators that may wish to eat them. A group of researchers in 2017 attempted to diagram the anatomy of the lobula complex in the brain of the mantis and compare it to other similar insects. I will not attempt to explain any sort of technical medical-adjacent concepts (although I consider myself an amateur biologist), but I will link the paper here for further reading: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5435961/

The real reason for reproductive cannibalism in mantis populations is only a theory, but one that makes sense in the grand scheme of ecology: food availability. After a female mantis, which is already much larger than the male counterpart and thus has larger metabolic requirements for sustenance, lays her eggs, it is estimated that she will lose up to a third of her entire bodyweight due to the immense size of the egg sac that must endure the harsh winter in order to produce nymphs in the spring after the first thaw. Because of this, the female desperately seeks replenishment, and having no discernment as to what’s right and wrong, savagely devours the first viable food source in sight - the one who got her pregnant. How fitting. Perhaps you really can have your cake and eat it too.